This will be my final post in the mini-series on paying for healthcare. I'd like to point out I don't really consider myself an expert on the economics of medicine, more of an interested observer, unlike science and medicine which I do think of myself as an expert on.

Hospital as airlines.

Another

article in the January Health Affairs considers whether hospitals in the United States are analagous to airlines before deregulation. Incredibly, the authors conclude that the answer may be yes, but this is a bad thing:

But competition can have a dark side. U.S. hospitals can treat Medicare and Medicaid patients at less than cost, care for the uninsured, and provide other money-losing services because they can cross-subsidize. By 2025 the need for general hospitals to cross-subsidize will greatly increase, but their ability to do so will be diminished. U.S. hospitals could begin to resemble U.S. airlines: severely cutting costs, eliminating services, and suffering financial instability.

I break down their argument into two parts: the need for cross-subsidies and the damage to the hospitals.

The cross-subsidy argument is basically that the health care market is so complex and inefficient that we shouldn't rationalize it. Sure right now government payors are probably charged less than fully-allocated cost (although probably more than marginal costs). But cutting costs and increasing efficiency could change that.

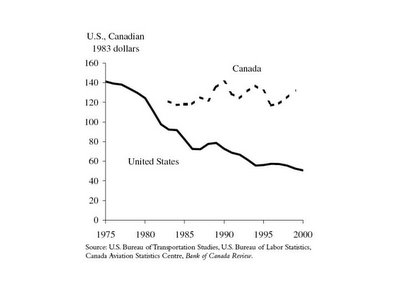

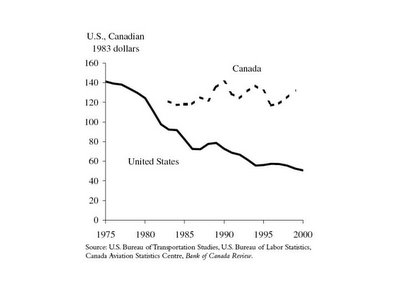

Imagine that in 1977 (before air travel was deregulated) the CAB required government employees on official business to be given a 30% discount. Would the government currently be paying more for airfare if the old system had stayed in place or paying full fare under deregulation. It's not even close. Airfares have fallen close to 60% since deregulation (figure from this

paper, in PDF form.

And service, at least measured by number of flights and cities served has increased as well (NYTimes article from last year via

Daniel Drezner):

At the same time, airlines have vastly expanded their networks, bringing air travel - a relatively infrequent experience [several decades ago] - to people all over the country. For example, American, the biggest airline, flew to just 50 cities in 1975; it now serves more than three times that number. Southwest, which started in 1971 with a single route in Texas, now flies to 61 cities, not counting those it serves through a code-sharing arrangement with ATA.

So the cross-subsidy argument is easily dismissed. Increased transparency and competition in healthcare will almost certainly decrease costs for everyone, even assuming the government will pay relatively more compared to commerical payors.

The second argument is that the change may be bad for hospitals. That may be, but I don't personally worry too much about that. If new, better, more efficient hospitals replace legacy ones is that really bad. Other than the luggage fiasco, flying

Southwest is fine by me. As noted above, the analogy to airlines decreasing their service is flawed. Air service has dramatically increased.

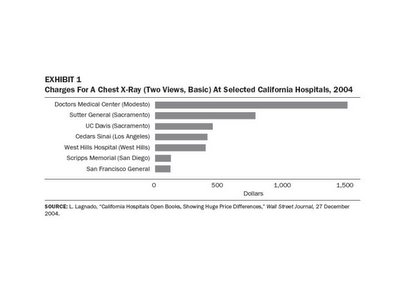

To give an example of the waste in our current health care, what if instead of charging $70 or $100 a day for meals patients had to bring their own? Already the food is so bad, many patients order out and surely restaurants do a better job of providing quality food at a good price. This is analagous to airlines which used to give you bad food as part of your inflated ticket price. I'd much prefer paying $100 less per ticket and eating before getting on the plane than the old way.

In summary, I think real competition among hospitals and in healthcare in general will provide better, cheaper care across the board. Will it be painful for many existing hospitals and health-care workers. Sure, as the article notes senior pilots make up to $250,000, new hires will top out at $100K. That is life in a capitalist society and we'd better get ready for it.